A newsletter to read, as we wait for the end of civilisation as we know it.

On the E-word we won't say, memoir writing, and psychology education training pathways.

Dear Bumblebees

It’s been a hot minute I know; 48,960 minutes in fact Google tells me, if we include my skipped newsletter last month. I sat down to write my newsletter last month and realised that I didn’t have much to say, but more to the point, was also just tired of saying things. Sometimes you get sick of the sound of your own voice, of your constant need to opine, and you start to laugh at your belief that you are anything other than a little tiny blip in the wide cosmos, soon to blink out (in cosmic years!). That’s where I was (and am) and where I often find myself, especially when I look at the razzle of social media. I know this makes it sound like I am depressed but I am not, indeed, I am quite purposeful and settled at present. However, I do find reminders of my own mortality and relative insignificance paradoxically settling and freeing, as it gives me permission to lurch on with my activities in the wide world, knowing that what I do probably isn’t as important as I think.

I recognise that many of us are feeling unsettled at the moment as the American E-word draws closer. My mental state is currently sitting along the lines of “what the fuck” when I realise that approximately 50% of those polled say they will vote for Trump. This seems unfathomable to me, so divorced from my inner-city leftie reality (I know what a bubble it is…), and such an indictment of the impact of fear left to run untrammelled. While a Trump win won’t directly affect me in Australia, this shifts the Overton window and brings far-right voices a little closer to the mainstream. I especially worry about the rise of fear-based, nationalist politics, and the untiring, tiresome attempts to control the female body. Atwood got it right when she wrote the Handmaids Tale.

Hold tight to your rights and civic responsibilities, vote with caution, remain skeptical, don’t let the voices of scarcity take hold; and hold humanity and the planet close. That’s all I have, paltry an offering as it is.

Memoir writing

I’ve signed on the dotted line, and will be writing a memoir for Scribe! Release date unknown, probably sometime in 2027/28. I’m enjoying this process very much, though the pace is far slower and more staccato than my usual non-fiction writing about mental health. Much more percolation needed.

Writing creatively feels like a return home (I used to do a lot as a child), and I’m trying to use this time to learn as much about writing so I can then launch into writing fiction manuscripts. The ideas, they are positively TEEMING. The beauty of a memoir is that there is no plot or story to generate — it’s all there — so you can focus exclusively on the technicalities, the pacing, structure, characters, dialogue. Writing is essentially about creativity and meaning-making for me, and pushing myself to extend in a different direction is a delight.

I don’t have the time to formally study writing, but I’ve been reading a lot about writing and have especially enjoyed Graeme Simsion’s The Novel Project, and Ursula K. Le Guin’s Steering the Craft. I’m also re-reading Margaret Atwood’s On Writers and Writing, and delighting in her erudite prose, so full of deep noticing and broad thought.

Psychology Training: Do psychologists feel ready to practice when they graduate?

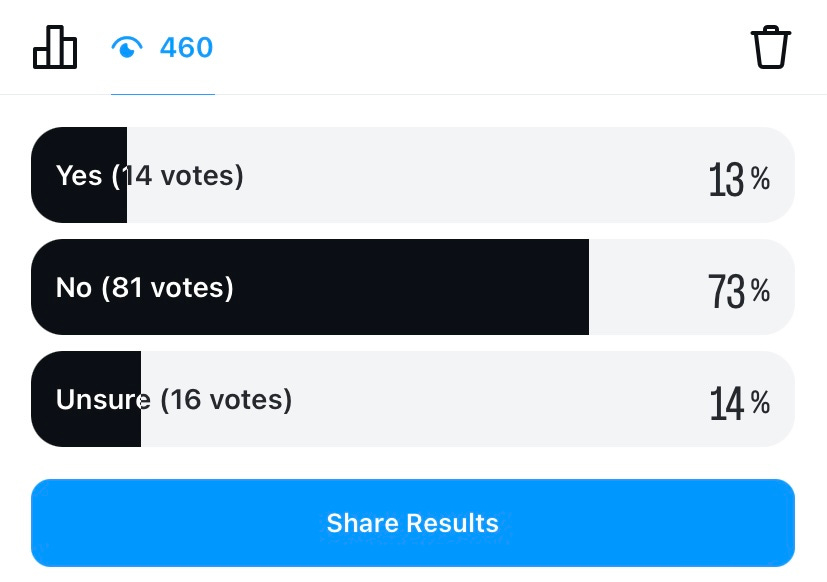

Those of you who follow me on Instagram will know I ran a poll a while ago, to see if psychologists felt like they were adequately prepared to do the job of a psychologist upon graduating from postgraduate study. 110 psychologists responded, and 1 nurse (thanks, friend). Overwhelmingly, people said that they did not feel ready, or were not sure if they were ready. This was certainly my experience too, and I want to unpack this a little. I also asked people what would have helped them feel more prepared, and the consensus was more training in therapy modalities beyond CBT.

Now, while this might seem alarming, there are a few things to note. First, the sample might well be skewed, and I didn’t collect any information about levels of training etc to allow more fine grained analysis (look, data collection is not my strength). Second, feeling unprepared is not the same as being unprepared. I suspect many mental health professionals are magicians at conjuring up imposter syndrome and will feel ineffective and incompetent though they are competent. Third, the gulf between being a student and practicing independently in the real world is massive — and I suspect that this shock drives some of the results. Most health professionals experience this rude awakening, psychologists are not alone.

Nevertheless, these results are concerning and speak to the difficulty psychology has faced with establishing appropriate training pathways, especially with the bulk of undergraduate study being taken up by theory heavy subjects. I’m sure these theories were valuable grounding, but I have to somewhat ruefully confess that I have forgotten most of them now, and that they have little overt bearing on the actual work I do now. I even had to ask someone to remind me what a Bobo doll was the other day! Theory is essential, but our degrees are theory-heavy at the cost of practice.

I did a dual clinical and forensic doctorate myself, and as I was contemplating my own training and how prepared I felt, I realised that oddly, I felt confident and well prepared to be a forensic psychologist, but not prepared to be a clinical psychologist. I attribute this to a few factors. First, my forensic training was top-quality and was delivered by forensic psychologists who work in the field daily. The course structure was newly instituted, well thought-out and structured systematically and thematically, with each main forensic issue covered in some detail. Case studies were used regularly. Our essays and assignments were interesting and topical, and our placement program was rigorous. I did a large placement within a team at Forensicare (where I still work), and this placement was transformational in helping me find my feet. I had in-depth weekly supervision, and lots of scaffolding. While I still had lots to learn, I felt like I emerged with a baseline and could operate competently.

The clinical training I received did not prepare me as well. I was largely taught by career academics and researchers, not practitioners, and the course structure and content had not been revised for a long time. Much of my training focused on theory (how many people get better after a course of CBT-P and how many relapse, studies of the evidence base for interventions), rather than actually learning or practising the interventions. The only formal training we received was in CBT. We skimmed over the basics of counselling (how to start a session, how to build the frame of therapy) and spent too much time on esoteric questions (e.g., how to ask the ‘miracle’ question — something I rarely use in practice myself). The course structure was overly academic and some subjects focused on theories which had little practical application (e.g., child development was focused on issues like learning the Piaget stages, with almost no exploration of matters like diagnosis of neurodivergence), and the placement and coursework programs had little linkage. I was lucky to have an excellent supervisor for my first placement who worked in private practice, but I was only able to see her fortnightly which was nowhere near enough at this stage. Many others had poor supervisory experiences with supervisors who did no clinical work themselves and were vastly over-stretched (a problem common to academia sadly). My last external clinical placement was excellent, and I was able to learn a lot about how to actually do therapy from my supervisor. Overall, I left feeling slightly prepared, but also with some big gaps in my knowledge, especially around how to actually treat a client for a mental health disorder — you know — that little thing clinical psychologists are meant to specialise in.

Repeatedly, this is the complaint I hear from my own supervisees now.

I don’t know how to treat someone, I don’t know how to do trauma treatment, I learnt about the evidence base for the therapies but not how to do them. I don’t know how to treat OCD, phobias, or eating disorders. Or perhaps; my client has four diagnoses, I don’t even know where to start, I was only taught to do CBT when someone has mild depression with no co-morbidities. Or, I know absolutely nothing about private practice and the business of psychology.

The practice of psychology is divorced from the education many of us have received. I highlight this to normalise the sense of disquiet most beginning psychologists feel, and to reassure each early career psychologist that you are not uniquely inadequate or flawed, you just need a lot more training than you’ve received. I’m not in the business of academia or designing course structures so I will not offer any suggestions there, instead, I’ll offer some suggestions for the beginning psychologist flailing around alone.

First, remember that you do know more than you think. You’ve learnt a lot about assessment, a little bit about therapy and you know how to start and run a session. Remember that forming a relationship with a client is key — it isn’t everything and you do also need to know what you are doing in the room, but it’s ok to focus on the relationship and leverage that as you scramble to learn other therapies. You will need to put in some hard work, your education has not ended. the good part? None of it is graded.

Find a good supervisor. This is essential. Whether you are doing the registrar program or not, you’ll need someone you trust and someone who can provide therapeutic, business, ethical and practical know-how. Shop around, interview, and find the right fit. You want someone you can be honest with. Don’t slack on supervision now, because bad habits once formed are really hard to shake.

Find the right role. I’m a huge fan of working in public mental health initially. You’ll have the support of a team, an established registrar program and lots of training provided. Eventually, you may want the diversity and depth of private practice, but starting out in private work can be challenging. If you do decide to go into private work, I recommend finding a clinic which has a history of supporting registrars. I am adamantly opposed to psychologists launching into solo practice in the first two years after graduation, because there’s no oversight or accountability and training.

Start with the basics. How do you start a therapy session? How do you develop a real-life treatment plan (no, not that neat 4-session CBT plan you wrote for uni)? How do you formulate repeated non-attendance? How do you communicate a cancellation policy to clients? How do you identify transferential processes? How do you tolerate a client terminating? Which of your own schemas are present in the room with you? All of these are important questions to explore in supervision. Walk before you run.

Develop a training plan. I recommend attempting to learn one new form of therapy each year for the first 3-4 years, and then starting to specialise based on your interests. Therapies like ACT, MI and DBT are excellent additional therapies to add to your toolkit of CBT. Therapies like schema therapy and IFS are useful when you have more experience or if you work with complex clients. If you want to work in a certain area, like PTSD or eating disorders, you must seek out appropriate training in first line therapies for these disorders (e.g., CPT, PE or EMDR for PTSD). Reading books is usually not enough. This training can be expensive, but I see this as an investment in the work I do, and essential to provide good care for clients, as well as important for my own longevity in this field — I won’t want to stick around if I feel like I’m doing my work badly! Revise this training plan regularly, and be honest about gaps in your knowledge.

I hope this helps new clinicians starting out. If nothing else, the knowledge that most of us felt this way can be reassuring.

STANDOUT OCTOBER READS (otherwise known as ‘Alas, Ahona is too lazy to make a list of all she’s read’)

Autobiography of a Face - Lucy Grealy

Martyr - Kaveh Akbar

Stone Yard Devotional - Charlotte Wood. Late to the party as always. Coming late and leaving early are my specialities. Not sorry.

MEDIA WRAP

I had this article published by the Saturday Paper on why dangerous therapists can be hard to stop.

I also had this article published by the Age about the Pelicot trial.

UPCOMING EVENTS

A Q&A at Kew library for Social Inclusion week on 25th November. Free, details here.

Resilience in Creative Practice, a webinar for the Australian Society of Authors on 27th November. Register here.

A webinar for the Australian Psychological Society on working therapeutically with victims and perpetrators of intimate partner violence on 11th December. Register here.

While there's so much going on in the world, I am pleased to hear you're getting on with your memoir at whatever pace it calls for.

May I also suggest: Bird by Bird by Anne Lamott for more nuggets of writing advice. It's one of my faves.